Rating:

# no-calm

`397pts` `90 solves` `Reversing`

-----

* *@author*: derbenoo

* *@note*: The original write-up is located [here](https://derbenoo.github.io/ctf/2017/09/24/backdoor_ctf_2017_no_calm/)

-----

## Challenge Description

h3rcul35 and starlord were having a heated conversation and to c00l down the furious starlord, h3rcul35 gave him a binary and said "The binary takes each 'character' byte of the flag as argument. Given this info, grab the flag. I hope you don't get angry :P". Show h3rcul35 that you stayed c00l by finding the flag.

## Overview

We run the binary and get the following prompt:

```

$ ./challenge

Usage ./challenge <each byte of flag separated by spaces>

```

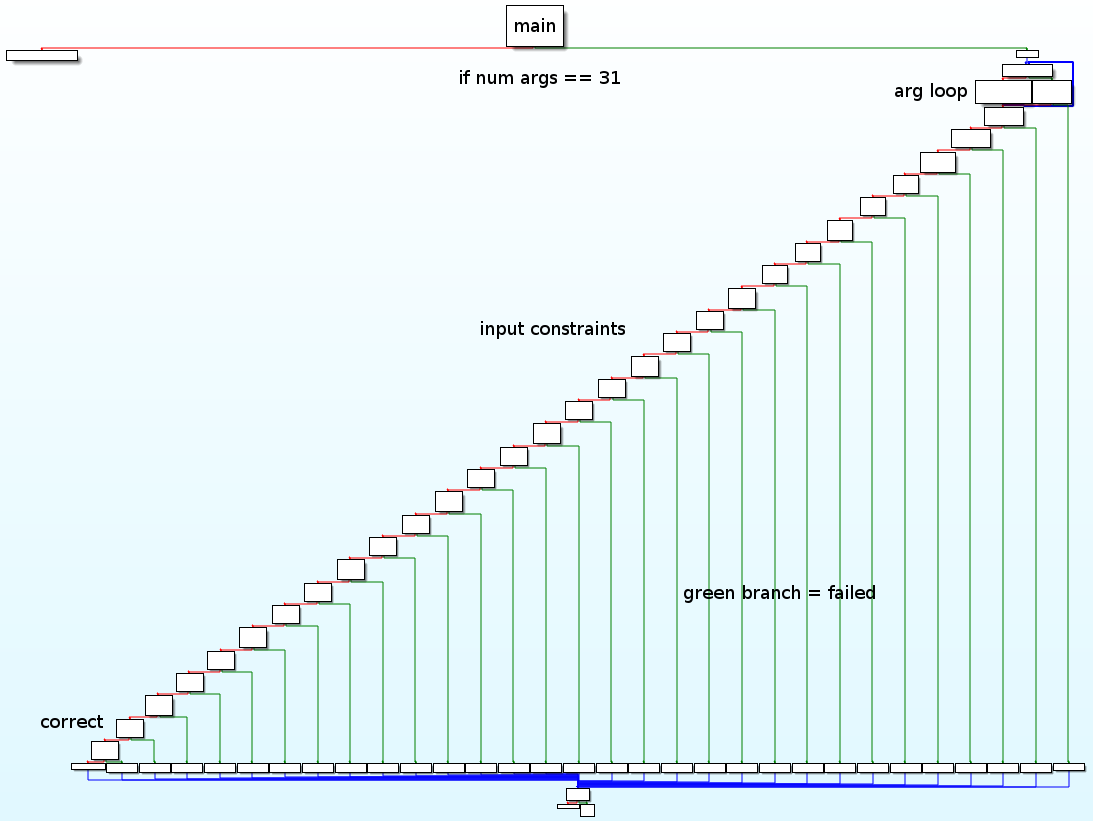

The binary is dynamically linked and not stripped, so we have an easy time understanding it in IDA. At the start of the program, the number of arguments is checked against the value 31. That leaves us with 30 arguments that we have to provide since the first argument is always the path of the binary itself. Using the output we obtained earlier, we can infer that the flag has a length of 30. The program continues to parse the arguments by iterating over them in a loop and storing the first byte of each in an array. Then follows a very long sequence of blocks:

Each block roughly looks like this:

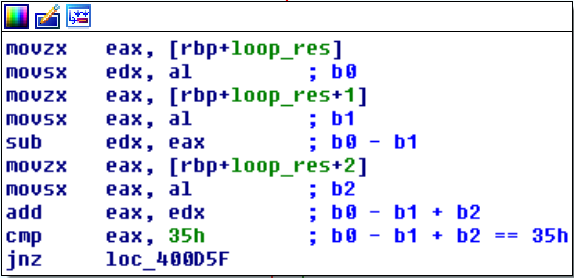

We skim through the blocks and notice that all of them have the following structure:

* `{add | sub}` instruction on two bytes of the input

* `{add | sub}` instruction on one byte of the input and the result of the previous computation

* `cmp` instruction with a constant value

So basically each block defines a linear constraint on the input values. While we could go through all the blocks, write down the constraint and solve the resulting equation system by hand, we choose to automate the process a bit.

## Extracting the Constraints

The first step can be accomplished by writing a GDB Python script. Let's go through it step by step:

``` python

# run like this: gdb -x calm.py

peda.execute('file ./challenge')

peda.set_breakpoint(0x40085E) # break before first input check

len_input = 30

input_stub= ("A "*len_input)[:-1]

peda.execute("run %s" % input_stub) # run with input stub

```

We load the challenge file and set a breakpoint before the first input check occurs. Note that the program is run with just a bunch of A's as input as we will replace them in the next step:

``` python

input_vals= ''.join([chr(i) for i in range(len_input)])

rbp= peda.getreg("rbp")

pedacmd.patch(rbp-0x30, input_vals, None) # replace input

```

The actual input bytes we want are `\x00, \x01, ..., \x1d`. We directly write them to the memory location our inputs are stored after the for loop (`rbp - 0x30`) since that is easier than trying to provide non-printable bytes as command line arguments to the program... However, you might wonder why we need these specific bytes as our input? Well, as it turns out this greatly facilitates our way of extracting the constraints from the assembly code by doing the following:

We know that each block defines a constraint. Furthermore, each constraint is defined over 3 of the input bytes where each byte is either subtracted or added to the equation and the result is compared to a constant value. We can use this fixed structure by writing a script that breaks on every `add`, `sub` and `cmp` instruction. However, in order to know which bytes of the input are referenced by the instruction, it helps to set them to the values described above. This way, we simply have to check the registers `rax` and `rdx` and the value that they contain will be equal to the index of the input byte that they reference! Let's start with a while loop that runs until we reached the end of the constraints section:

``` python

constraints= [] #store constraints in a list

rip= peda.getreg("rip")

constr_count= 0 # we need 3 instr per constraint

constr= ""

while rip < 0x400C70: # run until hitting the "hacked" part or failure

rip= peda.getreg("rip")

instr= peda.current_inst(rip)[1]

```

We initialize the variable `constr_count` to keep track of the number of instructions that we have already seen for the current constraint that we are building in the `constr` variable. We continue to check for the three instructions that are interesting for us (and the `jne` instruction):

``` python

if "add" in instr:

if constr_count == 0:

# first calc for this constraint -> extract both operands

eax= peda.getreg("rax")

edx= peda.getreg("rdx")

constr= "b[%d] + b[%d]" % (eax, edx)

elif constr_count == 1:

# second calc for this constraint -> extract one operand

eax= peda.getreg("rax")

constr+=" + b[%d]" % eax

else:

print("ERROR occurred at address %s" % str(rip))

peda.execute("quit")

constr_count+=1

elif "sub" in instr:

if constr_count == 0:

# first calc for this constraint -> extract both operands

eax= peda.getreg("rax")

edx= peda.getreg("rdx")

if instr.index("edx") > instr.index("eax"):

constr="b[%d] - b[%d]" % (eax, edx)

else:

constr="b[%d] - b[%d]" % (edx, eax)

elif constr_count == 1:

# second calc for this constraint -> extract one operand

eax= peda.getreg("rax")

constr+=" - b[%d]" % eax

else:

print("ERROR occurred at address %s" % str(rip))

peda.execute("quit")

constr_count+=1

elif "cmp" in instr:

if constr_count == 2:

# extract const

const_val= instr[instr.index("0x"):]

const_val= int(const_val, base=16)

constr+=" == %d" % const_val

constraints.append(constr)

constr= ""

constr_count= 0

if len(constraints) > 32:

peda.execute("quit")

else:

print("ERROR occurred at address %s" % str(rip))

peda.execute("quit")

elif "jne" in instr:

peda.set_eflags("zero", True)

gdb.execute("n", to_string=True)

```

This looks like quite a bit of code but the logic behind it is quite simple:

* `add` instruction: If we encounter an `add` instruction, we simply add the referenced variable(s) to our constraint.

* `sub` instruction: We do the same as with the `add` instruction but have to be careful of the order in which the variables are referenced. We know that if the `sub` instruction is the second instruction for the constraint, the order of its arguments is always the same: First the result of the previous calculation and second the new input byte so we can simply read the value of `eax` and add it to our existing constraint. While this assumption might be a little of a stretch, it worked for this challenge ;)

* `cmp` instruction: Extract the constant value and add it to the constraint

* `jne` instruction: make sure we go to the next block by setting the zero flag

Finally, we print all constraints in a format that makes it easy for us to process them in our next step:

``` python

print (" -- CONSTRAINTS --")

for i, constr in enumerate(constraints):

print("model.addConstr("+constr+", 'cnstr"+str(i)+"')")

peda.execute('quit')

```

We let the script run and indeed, it successfully extracts all 30 contraints for us!

``` python

-- CONSTRAINTS --

model.addConstr(b[1] + b[0] - b[2] == 81, 'cnstr0')

model.addConstr(b[0] - b[1] + b[2] == 53, 'cnstr1')

[...]

```

## Solving the LP

Now that we have the constraints the program "defines" on the 30 input characters, solving the LP is straightforward. We make use of Python/ Gurobi and write a script that should do the job:

``` python

from gurobipy import *

model = Model("calm")

b= []

for i in range(30):

b.append(model.addVar(vtype= GRB.INTEGER,

lb= 0,

ub= 256,

name= "b[%s]" % i

))

model.update()

# constraints

model.addConstr(b[1] + b[0] - b[2] == 81, 'cnstr0')

model.addConstr(b[0] - b[1] + b[2] == 53, 'cnstr1')

[...] # add remaining 28 constraints here ;)

model.update()

model.optimize()

print repr(''.join([chr(int(var.x)) for var in b]))

```

We add 30 variables (one for each input byte) to the model and restrict their value space to [0, 256] to make it a little easier for Gurobi. The extracted constraints are then added to the model as well and after solving the LP (which takes basically no time at all), the script prints the flag :)

## Conclusion

Although the challenge description screams "use angr!", we successfully solved the challenge in our own way. Some parts of the solution are intentionally left blank as the challenges from the BackdoorCTF 2017 are transferred to a practice area for permanent hosting.