Tags: misc forensics audio

Rating: 5.0

Serial || 300 points || Forensics - Solved (1 solve)

----------------------------------------------------------

This challenge was pretty fun -- and very very frustrating when I had no

idea what I was doing or where to go next. *(I'm reminded of that time

when I accidentally mirror-inverted then rotated the QR code I was

trying to de-corrupt and decode, and so of course didn't make any

progress at all...)*

From the title 'Serial', it was pretty likely that this would be a

stream of serial data, so all I had to do was decode that, right? Super

easy, right?

Solving the challenge:

----------------------

### Scoping it out

I opened the audio file in audacity. This is pretty much always worth

doing for any sort of forensics-y audio file: often it looks interesting

either in the waveform view (if you zoom in enough), or in the

spectrogram view (check out both linear and log scales).

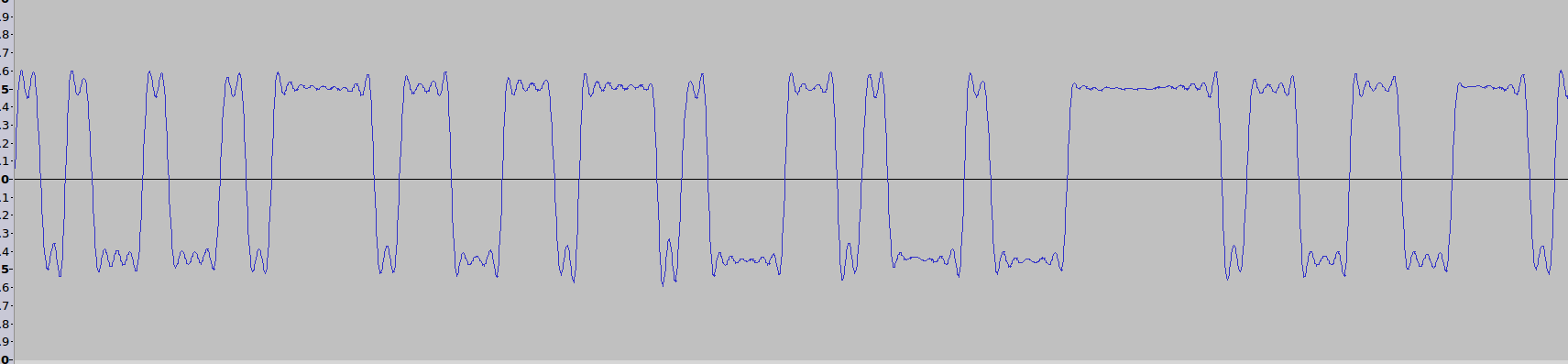

*Figure 1: screenshot of .wav opened in audacity. there are **very**

obvious high/low "values".*

Okay, cool, let's try to convert the low/high from the audio file to a

stream of 0s and 1s.

I started out in hexinator (fantastic hex editor, 10/10 highly

recommended for CTF stuff --

[*https://hexinator.com/*](https://hexinator.com/)) to check out the

headers/metadata (and get the offset for where the data started), and to

see if anything stood out in the raw bytes. *(You can also get the

metadata using `ffprobe`, and stare at the hexdump using `xxd`,

which could be better if you're in a hurry.)*

The wav file stored sounds as 16 bit values, which means they will range

between roughly -32760 and 32760.

### Pulling apart the .WAV file

I opened the wav file as raw bytes in python, started from the first

byte after the header ended, and printed them out to see if I could see

any obvious patterns -- ideally, it would be super trivial to get the

low/high out of the audio file.

```python

a = open("easyctf_serial.wav", "rb").read()

b = a[44:] # the header is 44 bytes long, skip to the data

# take every two bytes, and interpret them as a short integer, storing

# it in an array

raw_bytes = [struct.unpack('h', ''.join(b[i : i+2]))[0] for i in

xrange(0, len(b), 2)]

```

And, indeed there was: the numbers all fluctuated around roughly -1000

to -2000 for a while, then suddenly jumped slightly positive (300, 1000,

1400, 1650, 1400, 870) then suddenly very negative (down to about

-20000). They stuck around being very negative for a bit, then jumped up

to slightly positive, then back down to very negative, forming the

square-ish wave-y shapes seen in the picture above.

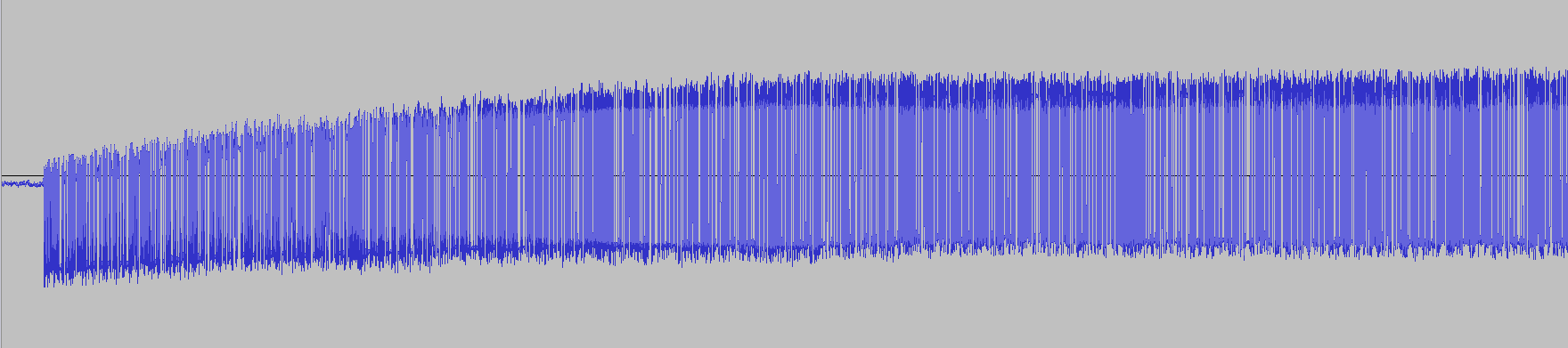

Unfortunately, there was no nice obvious cutoff for what defined low vs

high: you can see in the screenshot below that the 'low' starts out

pretty low, but the 'high' starts out barely above the centre line

(those slightly-positive numbers: maxing out at 1650 (out of a possible

max of 32760) initially.

*Figure 2: you can see that the audio file starts out with low/high being

shifted lower, then levels out to low/high being roughly symmetrical*

### Converting to 0s and 1s

I worked out the relative low/high based on where a given value fell

between the biggest and smallest values we'd seen thus far; through

trial and error, taking anything that was in the top 65% as high and the

bottom 45% as low worked out pretty well.

```python

for cur in raw_bytes:

# update bounds

if cur < c_min:

c_min = cur

if cur > c_max:

c_max = cur

pos = (cur-c_min)/float(c_max+1 - c_min) # avoid div by 0

# where are we in relation to the biggest/smallest we've seen so far?

print "%6d: %f | %6d %6d" % (cur, pos, c_min, c_max)

if pos > 0.65:

# we're in an upswing

print ">>> 1"

elif pos < 0.35:

# downswing

print ">>> 0"

```

Some sample output:

```

current_value relative_pos min max

1492: 0.974809 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

807: 0.944903 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-40: 0.907924 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-941: 0.868588 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-1804: 0.830910 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-2552: 0.798254 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-3089: 0.774809 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-3393: 0.761537 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-3405: 0.761013 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-3157: 0.771840 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-2658: 0.793626 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-1976: 0.823401 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-1168: 0.858677 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-338: 0.894914 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

433: 0.928575 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

1050: 0.955512 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

1428: 0.972015 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

1511: 0.975639 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

1249: 0.964200 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

618: 0.936651 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-364: 0.893779 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-1682: 0.836237 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-3271: 0.766863 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-5073: 0.688190 | -20836 2068

>>> 1

-6989: 0.604540 | -20836 2068

-8959: 0.518533 | -20836 2068

-10871: 0.435058 | -20836 2068

-12668: 0.356603 | -20836 2068

-14275: 0.286444 | -20836 2068

>>> 0

-15647: 0.226544 | -20836 2068

>>> 0

-16748: 0.178476 | -20836 2068

>>> 0

-17581: 0.142109 | -20836 2068

>>> 0

-18130: 0.118140 | -20836 2068

>>> 0

-18449: 0.104213 | -20836 2068

>>> 0

-18540: 0.100240 | -20836 2068

>>> 0

-18478: 0.102947 | -20836 2068

>>> 0

-18291: 0.111111 | -20836 2068

>>> 0

-18040: 0.122069 | -20836 2068

>>> 0

```

From here I disregarded the actual raw values, and just looked at the 0s

and 1s I'd bucketed them into. From looking at the wav in audacity I

could see that each bit was a certain duration of low/high, and multiple

0s or 1s in a row were a longer duration of low/high. So, I counted the

number of consecutive 0s or 1s:

```python

# this comes in handy later

def print_counter(counter):

print counter

for cur in raw_bytes:

# update bounds

if cur < c_min:

c_min = cur

if cur > c_max:

c_max = cur

if started: # disregard the non-useful section at the start

counter += 1

pos = (cur-c_min)/float(c_max+1 - c_min) # avoid div by 0

if pos > 0.65:

# we're in an upswing

if cur_val == 0:

# swapping

print_counter(counter)

counter = 0

cur_val = 1

elif pos < 0.35:

# downswing

if cur_val == 1:

# swapping

print_counter(counter)

counter = 0

cur_val = 0

else:

if cur < -5000:

# we hit the first drop

started = True

counter = 0

```

Sample output:

```

78

44

35

286

115

44

34

46

118

83

76

124

36

84

35

86

35

86

45

36

45

35

84

75

85

78

44

35

44

115

125

118

202

36

84

36

45

```

There was a pretty clear pattern here: the length of a run of

consecutive bits was roughly a multiple of 40.

So, I converted these to how many multiples of 40 they were, and

appended that many zeroes or ones to my stream of bits.

```python

def print_counter(counter, numbers, cur):

# print counter

num_multiples = (counter+20)/40

for p in xrange(num_multiples):

numbers.append(str(1-cur)) # flopped bits

```

### Decoding the 0s and 1s

Now that we have the raw stream of bits, it's time to try decoding it.

At first glance there wasn't anything obvious; I did some reading on how

serial communication and common serial protocols work, and discovered

that a serial stream probably has start/stop bits (and possibly also

parity bits).\

\

So, I set out looking for patterns: did the same value occur every n

bits?

```python

cur_val = -1

for interval in xrange(1,20):

for start in xrange(80):

failed = False

for upto in xrange(start, len(numbers), interval):

print upto

if cur_val == -1:

cur_val = int(numbers[upto])

continue

if int(numbers[upto]) != cur_val:

print "%d doesn't match %d (counter %d, interval %d, start %d)" %

(int(numbers[upto]), cur_val, upto, interval, start)

failed = True

break

if failed == False:

print ">>>>>>>>>>>>>>> success!!! cur_val %d, count %d, int %d, start %d)" %

(cur_val, upto, interval, start)

cur_val = -1

```

```

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> success!!!

val 0, count 12364, int 11, start 0)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> success!!!

val 0, count 12365, int 11, start 1)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> success!!!

val 1, count 12366, int 11, start 2)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> success!!!

val 0, count 12364, int 11, start 11)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> success!!!

val 0, count 12365, int 11, start 12)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> success!!!

val 1, count 12366, int 11, start 13)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> success!!!

val 0, count 12364, int 11, start 22)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> success!!!

val 0, count 12365, int 11, start 23)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> success!!!

val 1, count 12366, int 11, start 24)

```

Cool, we can see that every 11 bits, we have the pattern 001. eg:

`001XXXXXXXX001XXXXXXXX001`. Conveniently, 11 bits - 3 recurring bits = 8

bits = 1 byte of data = (y)

### Writing the raw bytes to a file

Time to write the raw bytes out to a file, and see if it looks at all

meaningful.

```python

byte_length = 11

ignore = 3

with open(files[0], 'wb') as filename:

filename.write(''.join(chr(int(''.join(numbers[

byte_length*k:byte_length*k+byte_length][ignore:][::-1])

, 2)) for k in xrange(len(numbers)/byte_length)))

```

That's a particularly messy blob of python, so, breaking it down:

* take our list of binary bits, in blocks of 11 bits at a time

* ignore the first three of those bits, and join the remaining 8

together

* reverse those 8 bits, because the bits are received in the opposite

order

* convert to an integer number, and then convert that to a character

* do that for all of the bits, then glue all of those characters

together, and write them to a file

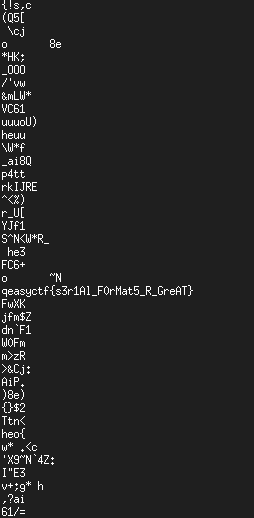

Time to see if there's anything useful in the file. run it through

`strings`, and `less` the output: there's a whole bunch of random

data, then eventually.....

*Figure 3: found the flag!*

By the way:

-----------

This is just the story of the things I did that **actually worked**. I

spent a lot of time trying a lot of things that didn't work in the

process:

* not finding the start/stop bits and staring into the void having no

idea how to progress

* not reversing the endianness of the bits

* inverting the bits so low is 1 and high is 0

* trying really really hard to find meaning in anything there

* failing very hard at decoding the binary by hand (everything looks

like a binary-ascii 'e' when you're desperate)

* trying to decode it using some sort of automated tool (and failing --

but hey it's 9600 baud, 1 start bit, no parity bits, 2 stop bits, so at

least I learned how to work that out and what that means)

In the end, I solved it by taking all combinations of `low=0 high=1` vs

`low=1 high=0` and `the order of the bits is least significant to most

significant` vs `most significant to least significant`, running all of

those through strings, piping all of that into less, and dramatically

scrolling through it looking for anything of significance.

(I didn't just `strings | grep 'easyctf'`, because that had failed before

and I wasn't expecting to find a flag, just hoping to find out some more

information on anything at all that might help me progress.)

Encore: solving the hint

------------------------

And now for the encore: there was a hint given for this challenge:

`1671272170308973364559718095536342710762555701423308167532544584`.

I spent a lot of time staring at it in frustration trying to work out

what it could possibly mean. They weren't ascii characters. There was no

obvious way to break it up into smaller numbers. Hm, but the binary

version looked interesting...

`1000001000000001001000001001000000001000001000001001001000000001000000001001000001000000001000001001000000000000001000001001000001001000000000000001000001001001000000000001000001001001000000000001000001001001000`

Look at how wide the 'gaps' are between each of the 1s. Looking at the

pattern....

```

5 8 2 5 2 8 5 5 2 2 8 8 2 5 8 5 2

1000001000000001001000001001000000001000001000001001001000000001000000001001000001000000001000001001

14 5 2 5 2 14 5 2 2 11 5 2 2 11 5

(1)000000000000001000001001000001001000000000000001000001001001000000000001000001001001000000000001000001

2 2 3

(1)001001000

```

There seemed to be some type of pattern going on here, and a friend

commented that they stood out as numbers that occured in the value of

1/7 (== 0.142857142...). This led to messing around with other bases,

and discovering that if you converted it to octal.....

`10100110110010101110010011010010110000101101100001011100010111000101110`

Would you look at that -- it's a binary string. And, would you look at

that... do I sense some ASCII?

Converting it to hex makes it a lot clearer: `0x53657269616c2e2e2e.`

(*sidenote: if you can't convert hexadecimal values to their ASCII

equivalent in your head, I highly recommend learning: in the very least,

if you can look at a hex (or binary) string and go "huh those are

printable ASCII values" it can speed things up a lot in CTFs. (also in

"cyber-crime" themed escape rooms.)*)

```python

>>> for thing in [0x53, 0x65, 0x72, 0x69, 0x61, 0x6c, 0x2e, 0x2e, 0x2e]:

... print chr(thing),

S e r i a l . . .

```

...... yep, I think they're trolling us a bit with that hint.